From Library to Mosque

The Story of Rahma Masjid in West Edmonton

t was Friday afternoon, just before jumuah prayers at Rahma Mosque in the quiet, west-end neighbourhood of Lessard in Edmonton. Issam Saleh walked across the street carrying a small package to two men seated in their car. The scene was common enough as Issam did this almost every Friday. He’d wave and knock on the car window, which they slowly rolled down.

“Hello neighbours!” he exclaimed with a smile. Issam’s family has deep, multi-family roots in the country and as a licensed public school teacher-turned-construction guru, Issam was strongly connected to the city as a proud Edmontonian. “Glad to see you as always. I brought you a sandwich and some chocolates for your time here.

”The driver in the car accepted the package while the passenger continued counting cars streaming into the parking lot and surrounding area for the weekly communal prayer. Rahma Mosque had been in the neighbourhood for a year at that point, taking up occupancy in the strip mall at the corner of 172nd street and 61st avenue in early 2010. These men continued to dutifully show up at the same time each week to assess the “damage” being caused to the neighbourhood by mosque congregants.

“You know, you’re welcome inside any time. You don’t need to eat in your car and we’d love to have you,” Issam continued. “We’re fine, thank you,” came the response as they rolled up the window.

“No problem,” he’d reply before turning on his heels, heading back to the shopping center-turned-prayer space to catch the Friday sermon and two cycles of prostration with hundreds of other worshippers.

The early days of Rahma Mosque, contained within the larger complex known as the MAC Islamic Centre, were characterised by patient community outreach and local friendship-building, continuously balancing joy at creating a special sacred place in an area which sorely needed it with the challenge of facing outrage for merely existing.

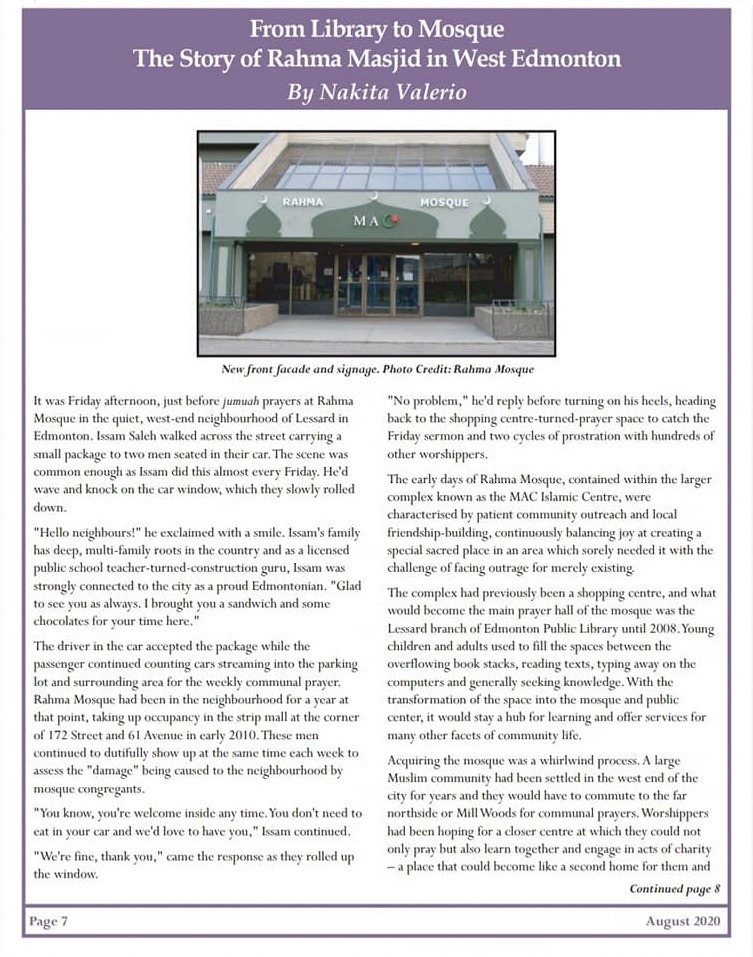

The complex had previously been a shopping center, and what would become the main prayer hall of the mosque was the Lessard branch of Edmonton Public Library until 2008. Young children and adults used to fill the spaces between the overflowing book stacks, reading texts, typing away on the computers and generally seeking knowledge. With the transformation of the space into the mosque and public center, it would stay a hub for learning and offer services for many other facets of community life.

Acquiring the mosque was a whirlwind process. A large Muslim community had been settled in the west-end of the city for years and they would have to commute to the far northside or Millwoods for communal prayers. Worshippers had been hoping for a closer centre at which they could not only pray but also learn together and engage in acts of charity — a place that could become like a second home for them and their families. It wasn’t until late 2009 that the Muslim Association of Canada (MAC) began looking earnestly for a center to fulfill these wishes and also establish the organization as a major player in the city’s Muslim landscape.

Established in the late 1990s, MAC was founded as a grassroots organization with a national reach, establishing mosques, schools and childcare centres in fourteen cities across the country. The core MAC team at the time they were scoping out the Edmonton location included Issam Saleh, who remembered that the almost-abandoned shopping center was owned by Servus Credit Union, but also that it was falling into a state of disrepair. The lack of outdoor lighting and vanishing tenants made the building an eyesore in the quiet, family-oriented community.

“It was actually a magnet for late-night drug deals and other shady behaviour,” he recalled. “People in the community wanted something done with it.” Given the size of the building, its west-end location and the potential for it to become a complete, neighbourly hub with retail and professional spaces as well as the much needed mosque, early MAC founders saw past the shadowy parts of the space to its potential.

Once the organization made an offer on the property, the biggest obstacle was coming up with the funds. A small office was rented in the Callingwood shopping center and a core fundraising team was established, headed by Nida Ali who was hired in the fall of 2009.

“I was calling so many people,” recalled Nida, marvelling at how generously the community gave to the project in such a short period of time. “We had to use an old school phonebook to locate Muslim family names all over the city, trying to find people and Muslim shops in Edmonton to see if they could support the project. We didn’t have many tools to contact people beyond cold calling.”

Remarkably, donations, along with interest-free loans from individual community members, flowed in and MAC raised the two million dollar downpayment required to secure the property in record time. It would take a while, however, for the other two-thirds of the project costs to be secured. Back then, avoiding interest in such large investments was a challenge and then-chapter head for MAC Edmonton, Ali Assaf recalled the difficulties the group went through in securing the space. As a Muslim organization, it was paramount to abide by the Islamic religious edicts forbidding the use of interest.

“It used to take a lot of time to negotiate with the financial institutions and clergy themselves to make sure the contract was sharia-compliant,” Ali said. “It took months, not weeks.”

All of that patience and hard work, however, soon paid off and as soon as the ink had dried on the deal, the group got to work on transforming the building. A group of volunteers set about removing the wood panels that covered the outside façade of the building. Later, a crew insulated the walls and then they were finished with stucco. Outside lighting was installed and questionable business deals late at night completely ceased.

“There were some issues with the roof leaking and for a while, we had buckets catching the drops whenever the snow was melting that first winter,” Nida recalled. “To be honest, I was always worried going into work in the building because I never knew what issue I might find as we continued working on it.” Work was slowly done to move the washrooms to a more appropriate space on the outside of the main musalla, prayer hall, and decorative features were also added. Eventually, the old library awning was taken down and the blue paint around the doors was covered with more neutral colours.

“I remember the day we took down the signs was the first time salah, the prayer, happened,” relayed Issam. “A small group of volunteers stopped and went inside to pray. The whole place was upside down and we cleared a small spot.” He paused, “It was very emotional to be a part of bringing the new mosque to life.”

There was no opening ceremony for the monumental space as work continued on it gradually. The first sacred jumuah prayers, however, took place on February 26, 2010, shortly after MAC took possession of the building. Three or four rows of community members and volunteers lined up to hear the khutbah sermon by the imam and celebrate the new space together.

“No one knew about MAC and the new mosque at the time,” remembered Nida. “My colleague, Aminah and I went to Muslim shops all around the city putting up our signs so people would know about us. The first jumuah had less than fifty people.” Over time, those numbers would grow into the hundreds and even thousands for annual Eid prayers.

“I can’t forget the moment when the donated minbar was brought into the space a couple weeks later, also at a Friday prayer,” Issam continued. “The first athan, call to prayer, occurred and the donors brought the wooden structure in to be installed. It was so loud to bring it in and everyone was watching but it was a very joyful moment for all. I remember I thought to myself, oh my Lord, we built a mosque.”

The name for the mosque was chosen by consensus among the regular early congregants in the space. Ali and others passed out paper surveys which were dutifully received back containing votes between three suggested names. The term Rahma was ultimately decided upon, meaning mercy, grace or compassion in Arabic and signifying one of the 99 names of Allah, ar-Rahman, the Merciful One.

Ali was originally set on a different name but over time came to love Rahma Mosque, stating, “In hindsight, it fits the mosque perfectly. It became a mercy for the community and everyone involved.” Eventually, a new sign was erected bearing the Rahma name.

Getting everyone in the neighbourhood on board had mixed results in the beginning. As attendance at Friday prayers increased, so too did the number of concerned community members counting cars and filing petitions with the City against the presence of the mosque. Even though MAC managed several open houses in the community prior to their possession of the site, Issam noted how challenges were still brought forward, especially from the Lessard Community League.

“We just parachuted in because the deal happened so fast and we didn’t have enough time to network with our neighbours as we normally would have,” explained Issam. “They just woke up one day and there was a new mosque.” Recognizing that the organization would be battling against general and expected discomforts, along with stereotypes against Muslims and concerns based on implicit biases, Issam noted that despite three years of difficulty with the League, “We, at the Mosque, never let them exhaust us. We believed in building a better neighbourhood for everyone and eventually they saw that too.”

Ali added, empathetically that, “The community league was worried we were going to crowd the place and not park well, blocking driveways, and coming through their backyards. They wanted the quiet cul de sac feeling. There are, of course, some people who monger hate and are Islamophobic but mostly the general public was concerned about what would affect them personally and they came around.” The mosque sent out letters to every nearby home, continued to hold open houses and invited the neighbourhood to beautiful events, especially in Ramadan.

One year, early on, at the annual Joy of Ramadan gathering, representatives for Edmonton Police announced that the presence of the mosque had brought crime in the neighbourhood to a total standstill. Eventually the opposition from the community ended as residents recognized how the mosque and community centre had brought a dead spot in the neighbourhood to life again.

Nearby interfaith allies included clergy at Beth Israel Synagogue down the road, and St. Anthony’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church across the street, both of whom welcomed MAC into the neighbourhood right away – a strong relationship which continues to this day.

Intracommunity conflicts also brewed in the mosque as deliberate choices were made to have little separation between the gendered prayer spaces, to purposefully have women on the mosque board and especially to have children welcomed into the prayer space at all times.

“It didn’t come without hardship,” explained Issam. “I was called names by people asking why they can see the ladies, or why there is only one entrance for men and women. Any time you upset the status quo, this will happen but alhamdulilah, praise be to God, we had the vision, we knew we would get the heat and that was fine. This is what makes MAC different. We just keep pushing forward.” Eventually, the mosque came to be celebrated for its floor plan where women could directly see the imam, as they should, and the fact that it was a family-friendly space, much like the rest of the neighbourhood.

While some tenants, like the daycare, opened alongside the mosque right at the beginning, the centre soon attracted a variety of others such as a bakery and halal shop, professional services, a second daycare and even a restaurant, making the MAC Islamic Centre a hub for neighbours of all stripes, as well as Muslims from the southside and Spruce Grove, looking to pray.

When Issam, Nida and Ali were each separately asked what Rahma Mosque meant to them, they all replied, “It’s my second home.” Despite early issues in establishing the centre, ultimately, the community around Rahma Mosque came to see it as their own, changing the face of the neighbourhood forever.

Nakita Valerio is an award-winning writer, researcher and Muslim community organizer based on Treaty 6 territory in Edmonton. She is a graduate in history and Islamic-Jewish studies from the University of Alberta and has been a research fellow with the Tessellate Institute and the Institute for Religious and Socio-Political Studies. She serves as an advisor to the Chester Ronning Center for the Study of Religion and Public Life at the University of Alberta Augustana Campus.